WebRTC For Real-Time Communication

How do you make a call on the Internet?

Photo by Hannah Wei on Unsplash

Introduction

Have you ever wondered what exactly happens when you make an audio or video call on the internet? Have you ever wondered how your gameplay is instantly streamed to all your friends and theirs to you? In this article, we will explore the magic behind this strange but familiar phenomenon.

Here’s a scenario, you’re bored so you pick up your mobile device and jump on WhatsApp to have a call with a friend. You click the call button, your friend’s phone starts to ring and hopefully, they answer and release you from your boredom. Now once they answer, a connection is established and communication begins. You can hear their voice being transmitted through your device's speakers and you can also speak into your microphone and have your words transmitted to your friend.

How do you suppose this works under the hood? What exactly is happening? Let’s flesh out the requirements why don’t we? Here’s what needs to happen:

The first and most important thing is that your device needs to be able to find your friend's devices.

Both your devices need to establish a connection path or channel to communicate

The communication should be real-time and bi-directional.

Communication should be fast with low latency.

From the requirements we already know that HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) isn’t going to cut it. Why? Well, that's because HTTP is a uni-directional request-response type communication protocol. This means that only the client (your browser or mobile application) can initiate a connection to a server. The server, however, cannot send requests to the client. Communication from the server is always preceded by a request from the client.

Another option we could turn to would be WebSockets. This is a better option. Websockets are bi-directional. They allow client-to-server and server-to-client communication in a real-time manner. We still have a snag though. Websockets require a server which means that communication must first pass through this server and then be relayed to the intended client recipient. This takes a toll on latency as the data has to traverse extra hoops to get to its intended destination.

This, my friends, is where WebRTC comes in!

What is WebRTC

WebRTC (Web Real-Time Communication) is an open-source standardized protocol for sharing pretty much any type of data via peer-to-peer connection (client to client) in a real-time manner. The emphasis here is on peer-to-peer because this essentially eliminates the problem we face with WebSockets. It uses the UDP (User Datagram Protocol) to send data over the internet to increase efficiency. Now we need not go through the extra hurdle of going to a server and having the server forward the request. We can instead talk directly to the intended client. In this case your friend’s phone (technically, it’s the mobile app on the phone but you get the idea).

How It works

Alright, now we know what WebRTC is and the problem it solves but how exactly does it work?

What do we want? We want a shortest-path connection with low latency. A client-to-client direct connection.

WebRTC implements an ICE (Interactive Connectivity Establishment) framework to accomplish this behavior. ICE is a protocol to search for paths and decide on the shortest one to take by collecting and sharing ICE candidates (client identity information, IP addresses, and ports). When the ICE protocol is done collecting all ICE candidates, it has to share them with the prospective peer. It does this in a step called Signaling.

Signaling

This is an important step in the webRTC connection creation lifecycle. Essentially, the peers need to find a way to exchange identities with each other before a direct connection can be established. This step is managed by the SDP (Session Description Protocol). The SDP is a message that describes a connection session and ICE candidates (valid identities or IP addresses) available for connection. It starts with an offer type SDP. A client desiring to start a connection makes an offer to the signaling server and the signaling server shares it with other clients. When these clients receive this offer, they generate an answer type SDP which is also sent to the signaling server to relay to the offerer client. After this exchange is done, the clients will have each other's identities and the ICE protocol begins to attempt to create a direct connection between the clients/peers.

NAT (Network Address Translation)

In a perfect world, the clients who wish to communicate are in the same local network. In this case, the ICE protocol uses the internal IP address of the clients in their local network to open a channel for communication and life is good.

Most times, however, the clients/peers that want to communicate won’t be in the same network. For this reason, communication is blocked because our clients don’t even each other. Since they don’t know each other, their NAT firewalls reject their attempts at communicating.

Typically, when a device enters a network perhaps a WiFi network, the router issues the device a private/local IP address from its subnet (think of this as a range of IP addresses that make up a network where direct communication is possible) and keeps track of it using the device’s MAC address (hardware unique identifier). This becomes the device’s communication identity in the network. For example, client A could have a private IP of 192.168.0.123, and router A could have a CIDR (Classless Inter-Domain Routing) of 192.168.0.0/24 (This means that this router can have 255 unique IPv4 addresses). While client B could have a private IP of 10.10.1.3, and router A could have a CIDR of 10.10.1.0/24. You can check out this article to understand more about IP addresses and how they work.

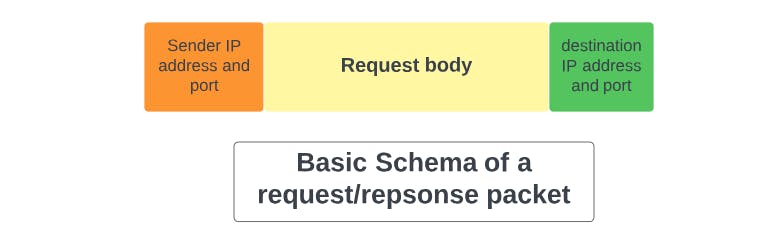

When the device makes a request to another IP address, the request is packaged into a packet with the IP address and port of the sender and destination included.

The request goes to the router first. The router then forwards the request to its intended destination IP and port. To do this a NAT (Network Address Translation) is done. The job of the NAT here is to keep track of the original requester (client) and map its IP and port to that of the router. It uses a pretty neat table to do this. This is necessary because at the point of forwarding from the router, the router becomes the new requester, and information about the client is lost. The destination server never actually sees the client as the requester but rather it sees the router as the requester. If the NAT doesn’t do its job, when the response gets back to the router it has no idea who the response is actually meant for and so the client never gets a response. This behavior is intentional as it enables the NAT to act like a kind of firewall where only IP addresses and ports recorded in its table have access to the network.

Okay, so we have a NAT now and can make successful request-response operations. Excellent! But it doesn’t end here.

The objective of the signaling step is to get all the possible IP addresses (ICE candidates) a client can be accessed through. Whether they are internal IP addresses, public IP addresses, IPv4, or IPv6 addresses. The NAT can help us to identify the public IP of our router network by employing STUN or TURN servers whose job is to package the IP address and port information as part of a response packet and return it to the router which returns it to the client. All the client needs to do is make a request to the STUN or TURN server. Voila! The client knows its identity.

Here’s the flow,

You're probably wondering what is a STUN or TURN server as you rightly should. Let’s find out!

STUN Servers

Session Traversal Utilities for NAT (STUN) is a server that basically allows a client to determine their valid public IPs. This is usually the IP of the router. This is achieved using the router's NAT table.

A client in a network usually has access to only its loopback address (localhost) and the internal IP address assigned to it when it joins the network. This internal IP is only useful for communicating internally within the network and can't be accessed by external networks without extra effort.

In the case of peer-to-peer communication, everything is fine when both parties are in the same network, the ICE protocol easily makes the shortest path connection using the local IPs of the clients. However, when they are not, we look to STUN servers for help. The client simply makes a request to the STUN server and receives its Public IP in the response. The ICE protocol then uses this public IP to communicate with other clients in external networks. Again, The NAT keeps track of the routing rules that allow the requests to the public IPs to reach their intended targets, the client's internal IP.

TURN Servers

STUN servers are great but sometimes, we could be faced with cases where communication is still being blocked despite the use of a STUN server. This could happen for a number of reasons like network firewall settings or NAT restrictions preventing direct peer-to-peer communication through NAT. TURN (Traversal Using Relays around NAT) servers offer an alternative path for communication that the ICE protocol can select. The servers essentially serve as a middleman between the peers trying to communicate relaying their data streams to and from each other thus bypassing firewall rules and NAT restrictions. TURN servers can be configured in different ways but we won’t be exploring them in this article. Check out this article by Gabriel Tanner to learn how to set up yours.

The final architecture looks like this,

Pros

WebRTC is open-source and standardized.

It is available in most recent browsers

It enables low-latency and real-time peer-to-peer connections

Cons

Nothing is perfect guys. Despite all its apparent capabilities, webRTC still falls short in certain areas.

It needs an extra server for signaling.

Requires STUN and TURN servers for communication over the public internet. These introduce management and cost overhead.

The peer-to-peer architecture breaks down as the number of clients increases. This is because the number of inter-client connections increases drastically. This takes a toll on the clients resources as they have to maintain n-1 connections at every given moment (n = number of connecting clients). Other architectures can be used to mitigate this but they usually involve the overhead of another server which is robust enough to handle all connections and relay streams appropriately.

Conclusion

We’ve covered a lot here guys. We uncovered the working mechanisms of webRTC. We explored NAT and NAT tables and how they can be used as firewalls. We talked about STUN and TURN servers and their relevance in webRTC.

Finally, we can answer our question, “How do you make a call over the Internet?”

If you have any questions feel free to let me know in the comments. Also, if you liked this article, don’t hesitate to share it with your friends and colleagues.